10 – Unloading Cargo and the Building of Scott Base

I would rather forget the next fortnight. We usually managed two tractor‑trips a day towing two sleds with about two tons on each, but there were constant breakdowns. Only Bates and I really had the experience to keep farm tractors rolling, our other Expedition members ranging from fair drivers to relentless destroyers of anything mechanical. One might be out eighteen hours, be in a bunk for an hour to be wakened by some clot saying "The tractor won't start!" (or,"the brakes won't work, the tow‑bar's broken, track's broken," etc etc). I still have a crescent and screwdriver dating from that period which I lived with.

The chain tracks wore out rapidly, especially if in contact with grit, and had to be replaced link at a time. Later we were to acquire rubber belting tracks which were much better. One night I gave my pet tractor Liz, to some idiot, to have him throw the keys at me a few hours later with some remark about it needing a look at. I pulled on overalls and went out on the ice‑edge. Liz was virtually destroyed! The tracks were piled on the first sled, the front wheels bent out of line, the radiator damaged and the bonnet torn off! It appeared he had stuck in a melt pool, and instead of working his own way out, had asked a passing US D‑8 to give him a tow!

The Americans had worse problems. Once I watched a SeeBee Chief showing some eighteen‑year‑old, straight out of a city, how to drive a D4 tractor. "Ya turn dis key to start, ya pull dis lever to go right, dis one to go left, and dere's da gears marked out on da floor. Now get to hell down to da ships with dese sleds!" A hundred yards away was an ice pressure‑ridge. The D4 roared up to it at full throttle, reared in the air, and fell over with a resounding crash, breaking a track frame! However, they had plenty of tractors!

I once suggested to an officer that they could save themselves $2 million a year by training drivers, and while he agreed, he claimed that if all this machinery were not destroyed, thousands would be thrown out of work in Peoria, Illinois! My suggestion that they just give a few Caterpillars to backward countries like ours was not taken seriously! At one point in the trail, opposite Hut Point, was a deep thaw pool about 4ft deep and a few chain long which could not be bypassed because of tilted ice‑blocks. Once I found it blocked by a D8 and two twenty ton sleds, tracks churning helplessly. I climbed aboard.

"Why don't you winch out?"

"What?"

"Winch. This thing! This is the clutch and this is forward‑reverse. I'll pull out your drawbar pin, you go forward on the dry land, I'll pull out the wire rope, and you winch the sleds over . Got it?" We went through all this with much crashing of gears, and he went his way without so much as a "thank you!" An hour later I was back and there was another D8, churning helplessly. As the ice was only 6ft thick, how one of those monsters never broke through I cannot imagine. Out at the site, the Base was being built at an incredible rate; the first hut was completed within two days by our M.O.W. engineers, and with four days we had two huts, power and hot water! Kiwis can work if they are motivated or competing to show they are good as an dam' Yanks. Meanwhile the dog party with Marsh and Brookes had given up the attempt to get up the Ferrar and the Endeavour moved across the Sound to the rescue. By this time the whole western part of the Sound was merely a jumble of ice‑floes, and having got as far as open water would allow, the doggoes sat on their sleds to await the ship which was forcing it's way slowly closer. The floes rocked and ground in the swell and George Marsh was heard to say;

"God! I wish the ship would get a move on!" This was so unlike the imperturbable Marsh that all eyes swung round.

"Why?" one said.

"I left my dramamines on board!" chortled George. "With all this swell I'm getting sea‑sick!" Soon dogs were being led up the gangway and sleds swayed aboard with Smithy in charge, and sounding real nautical. I sought out Mulgrew.

"What the hell is all this "Handsomely now; come easy as she goes!" talk of Smithy," I demanded.

"It means you're real Old Navy, it means you came aboard through the hawse when Nelson was flying yellow at the mizzen, it means stuff‑all." "Thought so". said I.

Actually I don't mind as of principle driving tractors or even repairing worn‑out tracks at midnight, in fact I once ploughed a wheat‑paddock that was a mile square at the rate of doing two rounds by morning smoko-break, but summer was passing and nothing much was getting done in the exploring line. If the Base was to be at Pram Point, then the only way to get up onto the Icecap was going to be up my pet Skelton Glacier. I hunted up Our Leader.

"Ed!" said I, "Now we are here, we'll have to use the Skelton. Why don't we fly out and take a look‑see!" He merely grunted. There is little doubt my mana was at an all time low because of the Butter Point fiasco, though how I was supposed to predict the worst thaw we were to see for many years beats me. It could have been worse, we could have arrived a month earlier, built the Base at Butter Point, and then been hit by the thaw. Mulgrew never lost a chance to make snide remarks until one day I picked up a spanner and gave him a look! Sir E simply never spoke.

The Beaver was swung onto the ice and we stood on fuel drums holding up the wings with our hands while Wally Tarr tapped in the half inch lock-pins and soon she was airborne. On the 18th after a weary night of repairing tracks and replacing a brake lining I fell into bed after breakfast, and woke after lunch to hear that Sir Ed, Bob Miller, Marsh and Brookes had flown in the Beaver with John Claydon to look at the Skelton and had landed at the lower end. They came back brimming with enthusiasm, they had discovered the way up to the Icecap! I seethed somewhat, which did not help visibly.

To rub it in, when I arrived back at Pram Point with a second load, Cranfield was full of a second flight he had made to the head of the Skelton. Interestingly, he had returned down my other preferred route down the upper Ferrar which comes out of the Skelton Neve. Increasingly, Bates was kept at Base installing generators and other hardware with Peter Mulgrew, while Hoffman and Mitchell, the MOW engineers supervised construction. At the ships (much of our cargo having come on the "Towle"), Randall Heke kept things flowing while I kept four tractors and usually at least one weasel moving, driven by any spare body to hand, including some of the summer party zoologists.

The ships galley staff were usually pretty good at finding a bit of food at odd hours as one could not possibly manage to arrive at the ship at meal times. One night however I arrived about eight after the evening meal was all tidied away and demanded tucker, but I was firmly told of several alternatives which did not include any likelyhood of food. A friendly and firm offer to "sort out the bloody lot of you!" resulted in a quick meal of mash and cold ham which did the trick.

On the 23rd Jan.,'57, I took a load out to Base in two hours, had a cup of cocoa in the new Mess Hut and was back at the ship for breakfast. Then came the news that the dog party, which had set out from Base around White Island and Corner Camp ( using Scott's old route to the Pole), but intending to then turn west to the Skelton, had run into trouble, George Marsh having collapsed with some bug. The radio not working as usual, Richard Brooke had sledged back 31 miles in 7 hours with the news and the Beaver went out and brought Marsh to the ship.

On my next trip, I passed a Weasel hurtling across the ice with a remarkable Father Christmas‑like figure seated on the roof and clutching the roof rack.

"Stop, damn you! Stop!" the figure cried, pounding the roof, and the weasel slithered to a halt. My friend, Capt. Hedblom, Surgeon, U.S.N. pushed back his home‑made red parka.

"Bernie, what the devil is this story about Dr Marsh?" I stepped down from the Fergie.

"Damifino," said I, "There is rumour that he has appendicitis."

"Appendicitis!" cried the good surgeon, "Good God! What the devil is a doctor doing down here with one of those? By God! We'll rip it out of him! Drive on! Damn you !Drive on!" (pounding on the roof), and the Weasel roared and lurched on.

"His bedside manner was perfect!" chuckled George to me later. "Here was I feeling pretty faint, when this incredible figure bounded into the cabin, hurled that awful red parka into a corner, then suddenly stopped, sat in a very dignified way, put his fingertips together, and said,

"Now, tell me Doctor, what appear to be the symptoms?"" It was finally diagnosed as diphtheria!

On Saturday came the news came the news that Richard and Murray Ellis had been flown direct out to a camp at the foot of my Skelton Glacier, the 180‑mile route round White Island and Minna Bluff having been short‑cut. The Beaver roared in and out all day carrying dogs and supplies with sledges and tents in the bomb racks, and then flying out Ayres and Douglas as well. I seethed some more, having enough conceit to take it for granted that I should be somewhere closer to all this action!

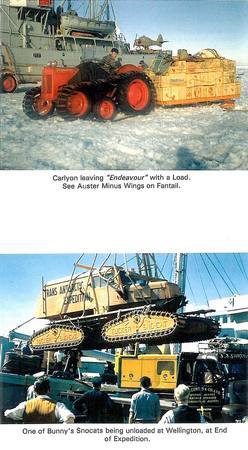

The ice was breaking up round the ships and unloading was delayed. Our Leader had abandoned one of our Weasels out at the American Ice‑runway, so Carlyon drove me out on a Fergie. We lashed the broken spring and I drove it carefully home. Down on our own airstrip was our other Weasel abandoned by Claydon with a broken track. I towed this home as well and Bates and I proceeded to create one serviceable vehicle out of the bits of two of them. A Weasel had, it seemed, forty points to grease (which only the conscientious Murray Douglas had so far bothered to do!). Fascinating! Weasel Three had badly worn sprockets due to overloading and had tracks and springs broken by bad driving. (The machines were numbered 3 and 5)

"These morons wreck 'em," snarled Bates as at the witching hour of midnight we grunted and heaved tracks about, "and we work all bloody night fixin' them!" The next day we happened to be visited by Paul Emile Victor, the French Explorer who had crossed the Greenland Ice‑cap using Weasels (the first crossing being done of course, by Watkins with dogs). He insisted a Weasel could go anywhere but had to be nursed by careful and skilled drivers. He had trained his men on the sand‑dunes of Brittainy. I thought it a pity we had not been able to do the same, all these continual repairs done outside was no joke though we blessed the fine weather. The Ross Sea Committee, abundant in absolute wisdom, had decided that we did not need a garage. Bates rumbled a bit about this.

"We gotta have a bloody garage," said he. "Lookit th' time we spend keepin' these bloody wrecks goin' even in summer! What th' hell will it be like in winter ! We got all them damn' tractor cases ain't we?"

"What about a roof?" said I doubtfully.

"We kin fabricate trusses or somethin'. Lookit all them waratahs some ijit brought down for snow fences. We got a bloody good weldin' plant!" At 1am I headed back for the ships. The road in the snow approached the Tide‑crack below Base diagonally and by this time had banks of ice five feet high. I eased our bitsa Weasel round and there was a clang as the left track came off the driving sprocket at the rear. I fear I swore though I am, I trust, not overly profane. Out came jacks and spanners and twenty minutes later, lit by a feeble midnight sun hanging over the dome of Mt. Discovery, we were ship‑bound again. Practice makes perfect.

By this time it was evident that I was going to spend the rest of the expedition as a full‑time rouseabout unless I exerted myself a bit. I approached Our Leader yet again.

"Ed", says I. "Someone is still going to have to sledge out to the Skelton from here to be sure the route goes. Why don't Guy and I take George's team, then we can do some geology when we arrive?" Sir Ed stared in some disfavour.

"Go and see George." he said finally. George Marsh, still recuperating on the ship, was not encouraging.

"Not to be thought of, m' dear chap," he said, weakly. "You and Guyon have no sledging experience, the dogs only half trained. No."

"Dammit, I have sledged here before!" George smiled faintly, "Yes. Forty miles!"

For once, I had nothing to say.

< Prev | Next >

©2007 - may not be reproduced without permission

|