6 – The Departure of the "Endeavour"

For publicity reasons, our good ship "Endeavour" ex "John Biscoe" was to make several official departures, from Wellington, Lyttleton, Dunedin and Bluff with some members joining at different ports. For some reason I was expected to be at all of them, though not joining ship until Bluff. She was not a lucky ship and of course that is what comes of the changing of a ship's name. What she was named on launching, let her stay says I. Little good came of renaming the "Cassandra" the "Walrus"!

At Wellington in early December, there were some farewell parties and one took place at the Town Hall where many of the school children who had raised money to buy dogs were gathered. Sir Ed and others spoke and as we left we encountered a phenomenon I had never seen before, autograph hunters. Sir E unhurriedly walked through the crowd and down the street, reaching out, taking autograph books and signing "E.P. Hillary!" without losing a step. On the street, he suddenly stepped off the pavement and by sheer pressure the crowd surged past. We took a few steps back and into a waiting car.

"You always have to have your escape planned!" said Sir E calmly. At that moment the door opened before the car had gathered speed and an extremely pretty fourteen year‑old with a very short skirt was in the back seat and on my knee.

"Would you mind?" she said holding out her book, and we signed with good grace thinking she had shown more than usual persistence. We let her off a few blocks away and proceeded to Parliament Building where we were supposed to meet Sir Sidney Holland who was Prime Minister at the time. We ushered into the Assistant Prime Minister's Secretary's office, then through the Assist. P.M's office, then through the P.M.'s Secretary's and finally into the Sanctum Sanctorum. Sir Sidney was most affable and poured brandy with a generous hand.

"Now you're a geologist," he said to me. "What's this stuff here!" and he picked up a piece of bright yellow mineral from a shelf an handed it to me. I hastily put my hands behind my back.

"It's Autunite, Sir," said I. "I'd put that down, its pretty radio‑active and you can get a radiation burn!"

"Yes, yes so they tell me, but what are they all excited about it for?" It was the time of the finding of Uranium in the Hawk's Crag Breccia in Westland and I guessed that that was where the sample came from.

"Well," I said cautiously, "It isn't that important now except for Bombs, but in about thirty year's time when we start running out of oil, uranium will be one of our main sources of energy." (Actually, that wasn't a bad estimate, though we knew little of Offshore oil at the time!

"Oh," said Sir Sidney, his interest fading. "Thirty years, eh?" and he replaced the sample on the shelf and changed the topic. Like all politicians his interest was limited to The Next Election due in a year's time (which he lost) and he obviously had no interest whatever in whether industry would be back to burning wood in thirty years or in any other problem so far in the future. In the event he died a couple of years later so who is to say he was not right? At Lyttleton I saw the "Endeavour" for the first time, she was an ex‑US Navy Net Tender of the kind my engineer brother had often done engine overhauls on in the early part of the war. She had been used as a sealer off Newfoundland and as a supply ship for the Falkland Islands Survey and she looked alarmingly small. One could easily swing a leg over her rail, step on the rubbing strake and step down onto the ice, if she happened to be alongside ice, without bothering about a ladder. She had a vertical stem and so could not ride up on ice if she struck it but had a sheathing of Greenheart wood added, Greenheart being supposed to be more resilient to ice than steel. It later proved to have been merely spiked on so was not much protection.

"Bet a foot of ice stops her dead!" was my reaction. She was far too small to carry all our personnel or cargo, much of which was going down in an American ice‑strengthened cargo ship, the "Pvte. John R. Towle". Our little Auster plane, now mounted on floats, was strapped on a stand on her stern from which it was supposed to be lowered into the sea for ice reconnaissance. Normally a Gipsy Major engine is hand‑started but ours was fitted with a device powered by shotgun shells to kick her over, it being hard to swing over a propeller while standing on a float covered in ice!

The Duke of Edinburgh, our Patron, had arrived in Lyttleton in "Britannia" and a number of social engagements were planned, the first being a wreath‑laying exercise on the statue to Scott on Oxford Terrace in the city. At least Prince Philip is the sort of person that no television cameraman ever born would ask to "Do it again!" Prince Philip came aboard "Endeavour" for an inspection and we were all lined up, presented and invited to dinner aboard "Britannia", which alarmed Dr George Marsh greatly as he affected to believe that all Colonials were totally lacking in the social graces, or so he pretended.

"For God's sake, men!" he urged. "Do try to remember that Chateau Lafitte is a wine, not "Bloody plonk " and please restrain yourselves biffing empties out the Duke's portholes!" We were to have our revenge.

It was a very formal meal, Sir E who had met Prince Philip before, was seated with him in the centre of a long table, and George immediately opposite with the Prince's equerry who had been to the same school as our medico. At the end of the meal, the Marines who waited on table, removed the heavy silver and brought us each a large plate on which was resting a finger bowl. A second Marine brought round a large platter with various fruit from which George, deep in a conversation about Old School chums, helped himself absently. Suddenly a quite audible "Christ!" was heard and all eyes revolved towards our George, staring horror‑struck at his fingerbowl in which floating half a dozen soggy and accusing strawberries!

Years later when Sir E was again dining with the Duke, he recounted the story.

"That's nothing!" retorted Prince Philip. "On "Britannia" I have known people to drink from the bloody finger bowls!" George, who had kept a close watch on the trendsetter of social customs and graces for the English‑speaking world, claimed afterwards that he was vastly relieved to observe that it was now socially acceptable to eat peas with a fork upside down and to refer in conversation to an aeroplane as a "Bloody kite". However, from that day on if George dared to comment on the oafishness of raw colonials, someone, usually Guy Warren, would interject quietly, "Been eating any strawberries lately, George?" and Marsh would grind his teeth in mock rage! Prince Philip was really taken by the Expedition and at one stage had some quite extraordinary plans to fly down by floatplane and join us in the pack‑ice. This was vetoed by Windsor Palace but he took "Britannia" down into Antarctic waters and visited Deception Island and cruised the Grahamland coast. On board among guests was Sir Charles Wright, who had been South with Scott in 1910 and had some absorbing tales to tell. Dinner over, we assembled on the dock to farewell both the "Britannia" and the "Endeavour" which was about to leave for Dunedin. Captain Kirkwood who had commanded her as the "John Biscoe" was on the bridge and so was friend Wilbur Smith, still carrying his list to port.

Perhaps someone had wined and dined too well, but what followed was inexcusable. Smith, leaning over the bridge ordered "Cast off Forward, Cast off Aft, Easy Ahead!" but overlooked was a spring leading well aft of midships. As this tightened, the stern of the "Endeavour" began to swing out to starboard away from the dock, towards the towering sides of a large freighter, the "Huntingdon". It only needed a touch astern to take the strain off to enable the spring to be taken in, or an axe in the hand of a competent bosun but no order was given and to shouts of "Look out for the 'plane!" the wing of the Auster shattered against the plates of the "Huntingdon".

Finally the ship steamed off to growled curses and already Wally Tarr had begun stripping it. However a replacement wing could not be found in time so we had no plane to use in the ice‑pack which cost us dearly in time lost. Ineptitude of this kind seemed to be a bad omen.

At Dunedin there were more festivities, the most notable being a dinner at Glenfalloch given by Mr Roland Ellis, father of Murray. He was an old friend of the family and much liked. He took me to one side.

"Now young feller!" he said seriously. "Look after yourself down there, remember you have that nice young wife to come home to!"

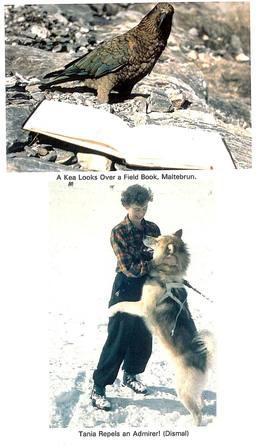

The "Endeavour" sailed with the evening tide, this time without mishap and Tania and I followed her down the harbour to the Heads with Colleen and Alec Black in the MV "Alert", and a day or two later we drove to Invercargill and Bluff to join ship. I walked up the gang‑plank half an hour before sailing and Sir E affected excessive relief. "Thought you weren't coming!"

We cast off at 11:30 pm on Friday the 22nd of December, 1956 and motored out into Foveaux Strait with its typical heavy swell. Some sang the "Maori Farewell" but I could see precious little to sing about as I leaned over the rail. A year and a half of hard work and no little danger lay ahead and while most of our party seemed competent enough, I had personal experience of almost none of them and who could tell how they would shape up after months of toil? Many had little or no experience of the conditions we were going to face, perhaps there were weak links in the chain and who could tell how many of us would return?

< Prev | Next >

©2007 - may not be reproduced without permission

|